New & now: Nosferatu

One of the things I like most about Nosferatu is how visceral it is.

I don’t just mean visceral in a gory way (though it is bloody), but visceral in the sense that you can almost smell it. Rot permeates every inch of Count Orlok’s crumbling castle, giving off a wet and sour odor, like when produce is left to go bad in a crisper. Under that, the sickeningly sweet scent of decaying flesh, countered with hot copper and petrifying wood. You can imagine what Orlok’s skin feels like, cold and too soft, not soft like a baby but soft like rotten fruit. And then, of course, there’s his voice: an otherworldly reverberation from deep in his chest that’s somehow everywhere and nowhere at once.

All of Robert Eggers’ movies could be described as visceral. The Lighthouse (still my favorite of his) is peak “I know it smell crazy in there,” and much of its atmosphere comes courtesy of the neverending rumble of both the rusting mechanics of the lighthouse, and the churning ocean. The Witch and The Northman both give a menacing pall to nature, and the feeling that it’s closing in around you. All four create a stifling feeling of doom, and being toyed with by something beyond your understanding.

Please allow me to be a pretentious a-hole and say that I’ve always strongly preferred the original Nosferatu over Dracula, even though it’s basically a rip-off of the novel created after the Widow Stoker refused to sign away the rights to adapt it. Except for Bela Lugosi’s legendary performance, which created the blueprint for nearly every portrayal of Count Dracula for decades (even though it doesn’t resemble how he’s described in the book), Dracula is a dreadfully dull movie. If you think Keanu Reeves is a boring Jonathan Harker in Francis Ford Coppola’s take, I invite you to watch David Manners’ performance, but bring a neck pillow and a blankie, because you will be asleep within fifteen minutes.

Now, Nosferatu isn’t exactly action-packed either, but it’s got one thing Dracula lacks, and that’s atmosphere. Death is everywhere in Nosferatu, whether literally in the form of thousands of rats invading a small German village, or just creeping along the edges of every scene. Eggers’ take on it amps up the action (and the violence), but maintains the calamitous spirit of the original, where darkness prevails and goodness won’t save you.

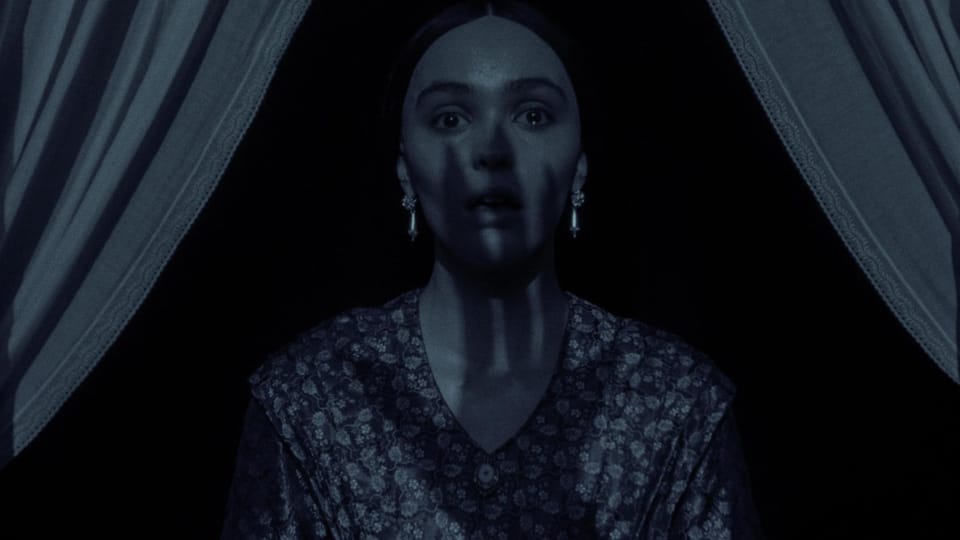

I’m not going to recount the plot beat by beat, because, like the original, it’s pretty much the plot of Dracula. Thomas Hutter (Nicholas Hoult), an ambitious young real estate agent, is sent to Transylvania by his eccentric boss, Herr Knock (Simon McBurney) to close a property deal with the mysterious Count Orlok (Bill Skarsgard). He’s forced to leave his newlywed bride Ellen (Lily-Rose Depp) in the care of their wealthy friends Friedrich (Aaron Taylor-Johnson) and Anna (Emma Corrin. The emotionally fragile Ellen is less than enthused about Thomas’s work trip, but Thomas, hoping to finally make a name (and some money) for himself, dismisses her fears and proceeds, setting the stage for a disastrous outcome.

If anyone was born to play a delicate early 19th century flower, it was the appropriately named Lily-Rose Depp. Even before things get rolling, Ellen looks like she hasn’t slept in a week, and her skin is almost translucent. Thomas’s desire to succeed in his job is understandable, but also this poor young woman looks like glimpsing a spider would send her staggering towards the nearest fainting chair. Ellen has long been troubled by dreams about a malevolent figure who haunts her, promising destruction and death but also inexplicably alluring at the same time. Nobody pays her much mind, however, attributing these dark flights of fancy to the “melancholy” she’s suffered from since her youth.

Here is one of the reasons Robert Eggers is currently one of my favorite filmmakers: his impeccable eye for historical detail, even though all of his movies so far are steeped in the supernatural. Though (as in the case of a lot of horror movies) Ellen turns out to be right about everything, her violent fits and rantings about death on the horizon are attributed by men to mental illness, and the treatments given to her, including leeching, being forced to wear a corset while sleeping, and restraints, while barbaric, are also historically accurate. When the well-meaning Dr. Sievers (Ralph Ineson1) suggests that Ellen’s problem is that she has “too much blood,” it’s not meant as an ironic joke (not entirely, anyway). it’s an accurate portrayal of the pseudoscience that passed as psychiatry before the 20th century. Even by the time Nosferatu takes place, doctors still relied on humorism (the belief that bodily fluids affected one’s mood and mental health) to diagnose emotionally unbalanced patients. To be diagnosed with “too much blood” was to exhibit behavior similar to what would later come to be known as bipolar disorder.

Eggers’ version also digs into a more distinct theme of classism, and its role in the eventual tragedy. Thomas is single-minded in his efforts to close the property deal with Orlok, even though there are numerous portents that this is an extremely bad idea (and not just the elderly Romani woman who begs him not to go to Orlok’s castle). In theory, it’s because he wants to make a proper home for Ellen. Still, there’s also a subtle (until it’s not) competition between him and the far more wealthy Friedrich, who generously opens his home to Ellen in Thomas’s absence, but not without a considerable amount of condescension.

Anna, his wife, is a bit kinder, but even she’s perplexed by Ellen’s bizarre behavior. She has little to offer Ellen as comfort beyond that she should pray for guidance, even though, as we eventually discover, praying is what causes all this trouble in the first place.

Is there more here than what you remember about the original Nosferatu? Oh definitely. It hews far closer to Dracula, with Friedrich standing in for Arthur Holmwood, and Dr. Sievers for Dr. Seward. As proof that horror fans will complain about literally anything, a minor but irritating ruckus has risen over the fact that Orlok has a mustache. Does it look weird? Kind of, but it also makes sense in two ways: (1) Count Dracula (and so, Orlok) was heavily inspired by Vlad the Impaler, who had a mustache, and (2) in the novel Dracula is described as having a mustache. Again, don’t come to a Robert Eggers movie if you’re not interested in historically accurate weirdness.

So no, I guess it isn’t a “faithful” adaptation of Nosferatu, provided you ignore the fact that Nosferatu wasn’t an original story in the first place. Eggers has incorporated some of the best aspects of earlier versions of Dracula, specifically the 1922 version of Nosferatu, Werner Herzog’s 1979 adaptation, and Francis Ford Coppola’s lush, overtly sexual 1992 take. Some of that sexuality remains here, but is far more repugnant, given Orlok’s monstrousness.

Perhaps it’s that repugnance that makes him so alluring to Ellen, even if she doesn’t understand why. She is a good young woman, and Thomas is a good young man. But, like young Thomasin is lured to the dark side with the promise of butter and pretty dresses at the end of The Witch, Ellen is lured by what her most secret heart wants: desire, decay, destruction, death.

This is the second movie this year after The First Omen (also a solid flick!) in which I’ve been surprised to discover that Ralph Ineson isn’t playing a bad guy. ↩

Member discussion